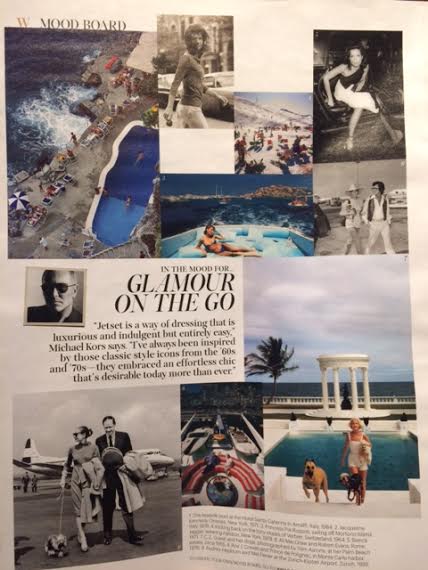

The value of art depends on many things — among other factors, the fame and reputation of the artist, the size of the piece, whether it carries the artist's signature, whether it is an original, a limited-edition reproduction, or simply a decorative print. Several years before his death in 1987, Andy Warhol sat down and signed his name on copies of the tabloid magazine Interview, of which he was the editor. Regularly costing $2, he charged buyers $50 for these signed copies and they sold pretty fast. As with much of Warhol's work, he wanted to demonstrate the public's all-consuming fascination with celebrity by highlighting those who would believe that his name had value in and of itself. But he wasn't suggesting that people revamp their thinking.

Walker Evans, Graveyard, Houses, and Steel Mill Bethlehem, PA, 1935 (printed posthumously)

The art print market is one where signatures count for a lot, and hundreds of artists have gotten on the bandwagon. An artist's name on a print can increase the price by two or more times, and creators generally view signing and numbering works as a valuable source of income for themselves. This is not to say that signed prints have intrinsic value only to the autograph hound. Many artists and dealers contend that by signing a print the artist approves and endorses it, and, implicitly, claims it as his or her own work. However, in most cases, artists have no more involvement in the technical processes of printmaking than simply tiring out their arms signing the finished works.

Dorothea Lange, Migrant mother, Nipomo, California,1936, (ca. 1985 printed) Photogravure

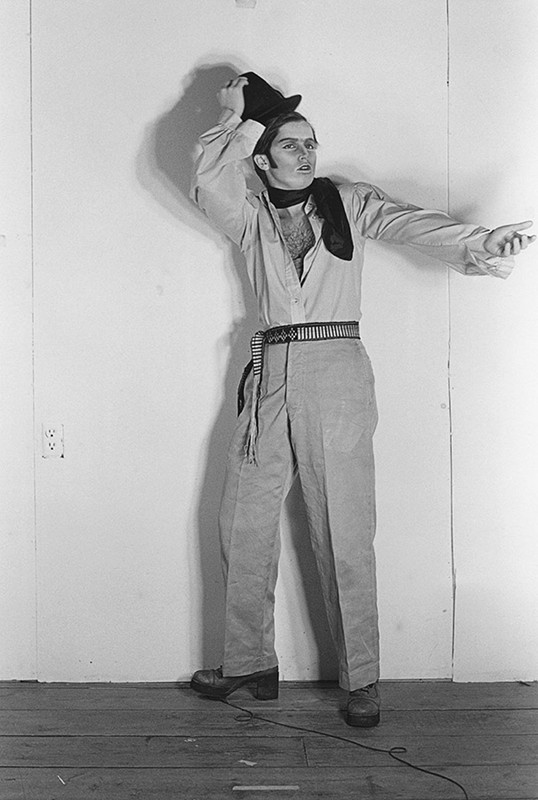

A work that wasn’t put on view during their lifetimes (and artists always produce more than they show and sell)? One has to assume that the artists knew best what they wanted presented to the public, and those pieces that didn’t make the cut may be kept around for any number of reasons. Scholars certainly appreciate the opportunity to examine artworks that reveal less well-known aspects of an artist’s thought process. However, when critics assess the piece of a sculpture or painting, their judgments never reflect negatively on the legitimacy of the art form.

Not so in photography. There, the posthumous intervention can undermine confidence that any photograph truly depicts an artist’s sensibility. “There is an endless anxiety on the issue of how authorship works in photography,” said Jeff Rosenheim, curator in charge of the photography department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in a NYTimes article from 2012 regarding posthumous prints .

When an artist passes away leaving behind unsigned art, that art has to be "signed" posthumously in order to authenticate it as having been done by the artist. In many cases, an "estate stamp" is made with a facsimile of the artist's signature, and unsigned pieces are stamped. Sometimes the art is estate-stamped and also hand-signed by a qualified third party; sometimes it is signed with the name of a qualified third party and not stamped; sometimes a qualified third party signs the artist's name instead of his or her own; sometimes a document or certificate is provided with each unsigned piece. From a marketing standpoint, none of the above outcomes are good. Dealers and collectors regard unsigned or posthumously signed works of art as less significant and desirable than signed works of art.

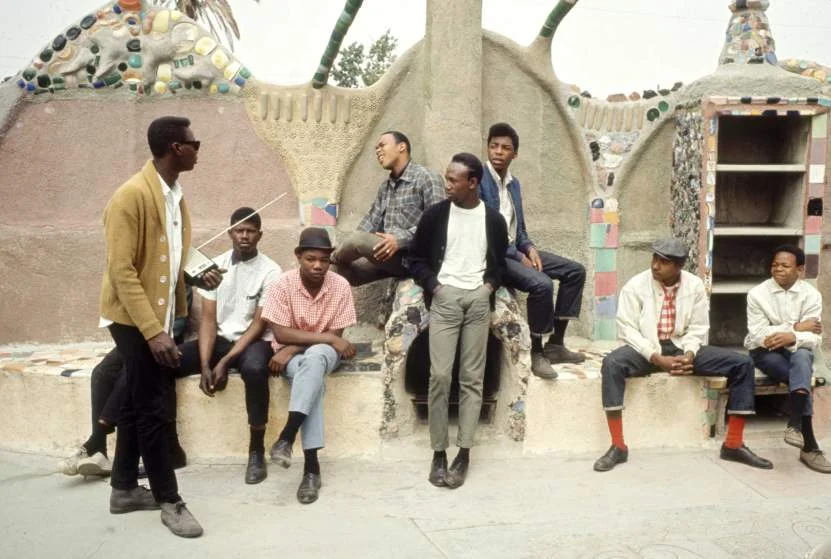

A growing number of photographers have gone back to their older negatives in order to see if something that didn’t appeal to them years back now looks better. For instance, photographer Cindy Sherman produced two series of prints in 2000 from images she took in 1976 (“Bus Riders” and “Murder Mystery”), and a number of photographs taken by Larry Clark in the 1960s and ’70s were printed by him in editions in the 1980s and ’90s. There is nothing illegal or unethical about this, and Sherman’s photographs are marked “1976/2000,” referring to the year in which the image was taken and the year in which the print was produced so that prospective buyers understand what happened and can judge for themselves. In fact, buyers do understand and make judgments, and the prices for what might be called “artists’ seconds” tend to be at a much lower tier than the highly valued vintage works of the earlier period.

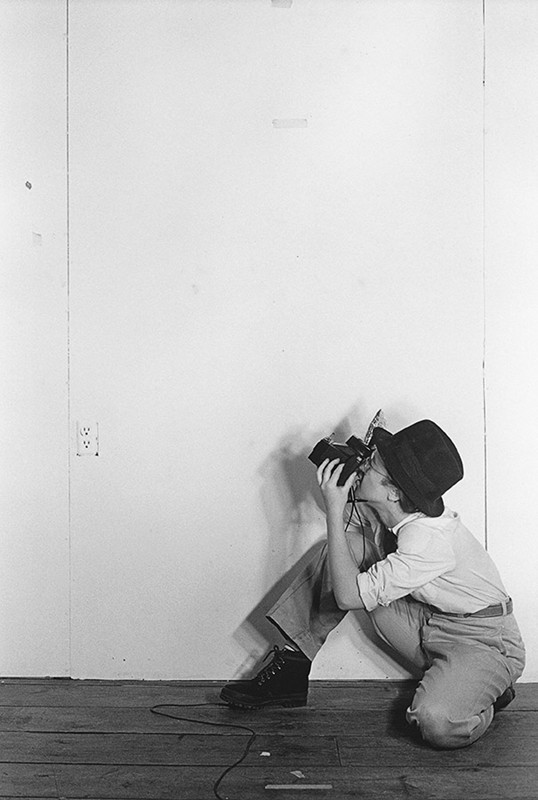

How can an artist evaluate his photographs, correct his working methods and present what best expresses his vision, if he has never proofed his negatives?

Certainly, posthumously produced photographs do appear on the market from time to time. The children and grandchildren of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston regularly sell newly printed versions of older, well-known images by these artists. However, these heirs identify on the back of each print when the images were produced and who did the actual printing, and the prices of these works are a few hundred dollars, not the five- and six-figure amounts that the ones made by these artists (or under their supervision) sell for in high-end galleries and at auction. Think of these prints as high-end souvenirs.

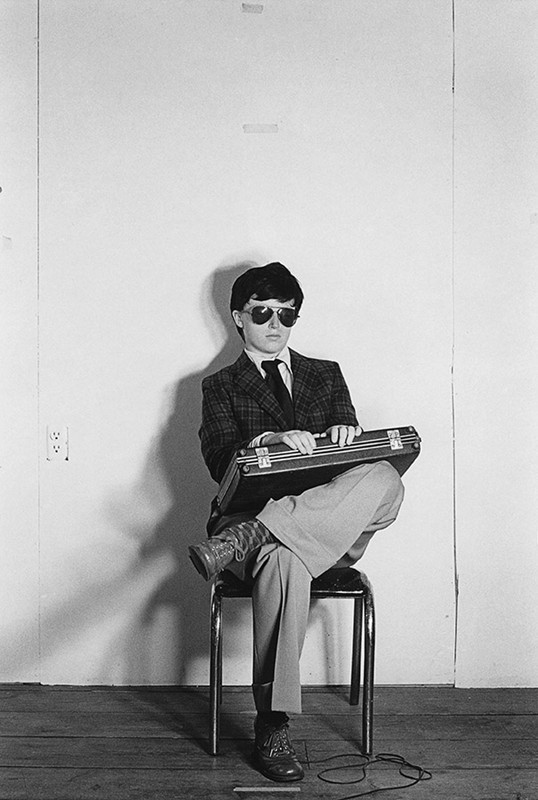

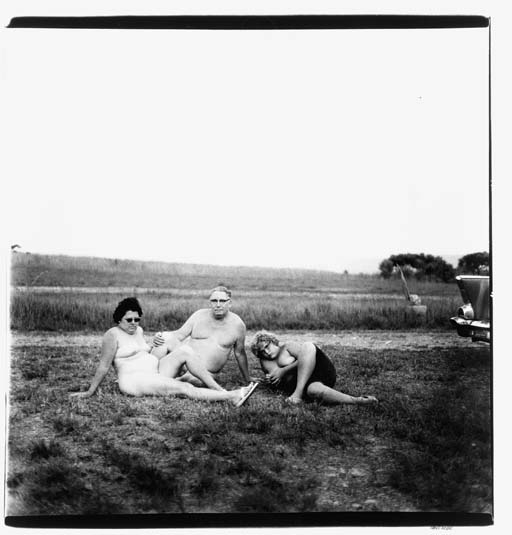

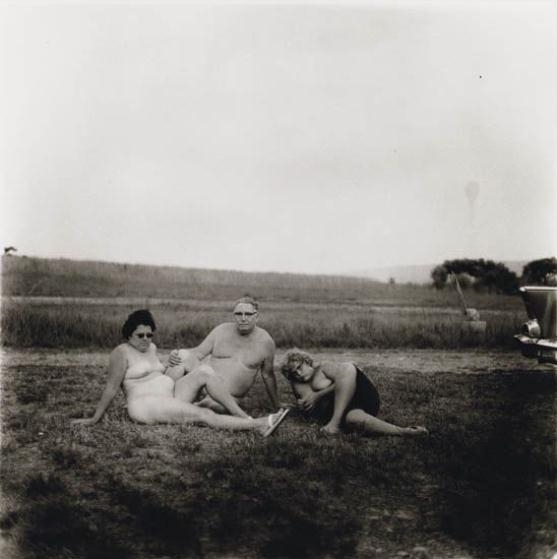

Above: "A Family One Evening in a Nudist Camp, 1965," silver print by Diane Arbus. The latter was printed in 1972 by the only authorized printer of Arbus' work, Neil Selkirk.

In the second category are posthumously printed photographs, sometimes referred to as estate, or Selkirk, prints, a reference to printer Neil Selkirk, with whom Arbus collaborated on a publishing project toward the end of her life. These are printed in the larger, 16-by-20-inch size and start at $3,000, but have reached $120,000 at auction, depending upon the reputation of the image and demand. Since Arbus's death in 1971, only one person--Neil Selkirk--has made prints from her negatives. All of Selkirk's prints have been made on the same humble enlarger Arbus herself used (illustrated on p. 272 of "Diane Arbus Revelations", the monograph accompanying the retrospective organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2003). The posthumous prints, generally limited to edition sizes of 75, are released with a certificate of authenticity, signed by Arbus’ daughter Doon Arbus, the executor of her estate. It is important to note that the edition number does not indicate that 75 prints actually exist. In most cases, the number is far less; sometimes as few as five prints exist from the "edition of 75."

Diane Arbus, Two Ladies at the Automat (New York City), 1966, Gelatin silver print printed by Neil Selkirk, 1977 or 1/77?

All Arbus photographs are technically offered to collectors on the secondary market, since the estate sells rather than consigns image. The value of these vintage prints is also somewhat dependent on their condition (some have creases and dents) and on the existence of a signature or other writing by Arbus that establishes authenticity and provenance.

Art and the art market are difficult enough to understand without adding the confusion of works that artists did not complete, may not have liked or were undecided about

There are two concerns — one immediate and one for the future. In the exhibition and catalogue (far more of them are included in the catalogue), these images are identified as the work of this artist. They are and they aren’t. When Garry Winogrand focused his camera and snapped the shutter, but much of the work of a photographer takes place in the darkroom, where images are cropped, tones are enhanced or lightened, and decisions are made about the developing process that will be used (silver prints, sepia tones, platinum, dye transfer — lots of options). For photography collectors, there also is a worry that these newly made images will be released as editions for buyers, muddying both the appreciation of Winogrand’s body of work and the understanding of what the artist produced and what others produced on his behalf.

Ysabel LeMay's phantasmagorical nature photographs defy all odds. In a world where nature photography has been done to death, LeMay' creates unique images that radiate with awe.